|

|

|

28:46 |

|

|

transcript

|

2:54 |

Hello, and welcome to 100 Days of Code in Python, written by Bob Belderbos, Julian Sequeira, and myself, Michael Kennedy.

Maybe you're wondering what is this #100DaysOfCode.

You've probably seen it all over social media.

In fact, it's really, really taken off and people are finding this concept of 100 days of code really powerful for getting them to focus over a long time to actually get over the hump, and become capable developers, or maybe learn a new language, like, say, Python.

Here's an example of what you might see on Twitter.

Rene Sanchez says, "Day 11.

#100DaysOfCode progress.

Today I worked some more on bite 18.

Find the most common word from codechalleng.es/bites." This code challenge platform they're referring to is actually from your co-authors, Bob and Julian.

We'll talk more about that later.

Here's another Tweet: "Day Five of 100.

Did some short exercises about modules.

Imported modules, did a couple of my own.

Tomorrow IO.

#100DaysOfCode #Python." Way to go, Bricks.

Here we have "Round one, day 101.

Had to do an extra day due to one day off sick earlier in #100DaysOfCode.

Today more Python debugging, tomorrow starts round two." And Jeff says, "Round one, day 19.

#100DaysOfCode.

Did three exercises in the book.

Basically my average, been taking it slow these last few days.

#CodeNewbiePythonIndieDevIndieGameDev" And finally, let's look at one more.

Amit Kumar says, "#Day32.

Another autowebcompat PR pull request, just got merged.

Way to go, Python Tkinter, #100DaysOfCode." So he added some new feature or bug fix to auto Web Compat, very, very cool.

So you've seen this stuff probably all over social media, Facebook, Twitter, and so on.

What's it about?

Well, this is actually a very structured project put together by this guy, Alexander Calloway.

So Alexander, he was studying in business school but also wanted to learn programming.

And he was having a hard time making progress.

So he came up with this idea of #100DaysOfCode.

Here's a quote from him: "The idea of #100DaysOfCode originally came from my personal frustration with my inability to consistently learn to code after work.

I'd find other less involved activities to spend my time on, like binge watching a TV series.

One of those days, I was sitting in a restaurant with my wife, and sharing my frustrations with her.

I suggested maybe I should make the public commitment to learning for at least an hour every day.

I thought it would go for three months, but it turned out 100 days was the right one." How about that?

Well, thank you for creating this project, Alexander.

This is really a great thing for many people getting started, and this is what this course is all about.

We're going to give you lessons and exercises for every one of these 100 days.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:05 |

There are a lot of things that people do to support each other and encourage themselves to stay focused and keep going on #100DaysOfCode.

But there's really just two main rules and they're really really simple.

The first rule is to code a minimum of an hour every day for the next 100 days.

And I would say taking a coding class like learning the lessons in this course and then coding a little bit counts, right?

You're immersing yourself in code for at least an hour a day every single day for the 100 days.

And if you got sick, like you saw the person before had gotten sick, had to take a day off, that's okay you just add some days on the end.

Have sick days and just move it to the end.

The second rule is a public commitment to making progress and keeping with it.

And they way that works is to tweet or to put onto somewhere like Facebook #100DaysOfCode with an update every day.

The PyBytes platform actually is going to help you a lot with this, but however you want to do it it's code an hour a day and share your progress every day.

Super simple rules, and we hope this course really makes this work for you.

|

|

|

transcript

|

3:06 |

We are going to cover so much content in this course, it's going to be amazing.

You'll learn many, many different things over these #100DaysOfCode.

In fact, there's so many I can't really enumerate all of them, it'll just take too long, but I do want to give you a quick sample into what we're going to cover.

We're going to talk about collections, lists, dictionaries, working with them.

We're going to test our code with pytest to make sure we build reliable apps.

We're going to create games, Dungeons and Dragons style with classes and inheritance and object-oriented programming.

We're going to deal with errors and proper error handling in Python.

We'll do logging to keep a history of what our application has done.

We're going to work with the popular exchange format called JSON, and it's a really great way to exchange data between Python applications and any web service.

Speaking of services, we're going to learn how to call JSON based web services from Python, and if there's no service, can still go to the website and do web scraping.

You can turn any HTML page, anything on the internet, into a data source using web scraping.

Another source that we might go and consume, RSS feeds, really popular among blogs and podcasts, but also other types of subscriptions.

We're going to use the Twitter and the GitHub API to interact with those services automatically from Python.

Want to send an email?

Maybe a new user registered for your site, well we'll see how to do that as well in this course.

Excel has got to be the most popular database in the world.

It's not really a database, but people use it like one, and you may need to program against it.

Turns out, we have the trick for you right here.

Want to automate something on the web?

Go login here, navigate over there, click this button, make that thing happen.

We'll see how to do that with something called Selenium.

You want to write a web application, well we'll do that with something called Flask, it's probably the easiest way to write a web app in Python.

SQLite is a database built into Python, it's what's called an embedded database, and you'll see how to program it, either directly, or from what's called an ORM from SQLAlchemy where you create these classes and you map them to objects in your database, so we'll have a couple of places where we talk about SQLite and relational data.

Graphs are wonderful, they explain so many things, and so we're going to use something called Plotly and draw graphs for you, based on a set of data that you have, and typically when you're doing science like stuff like this, that's done in something called Jupyter Scientific Notebooks, and a good portion of this class will be presented in these notebooks.

Not all of it, maybe about a quarter.

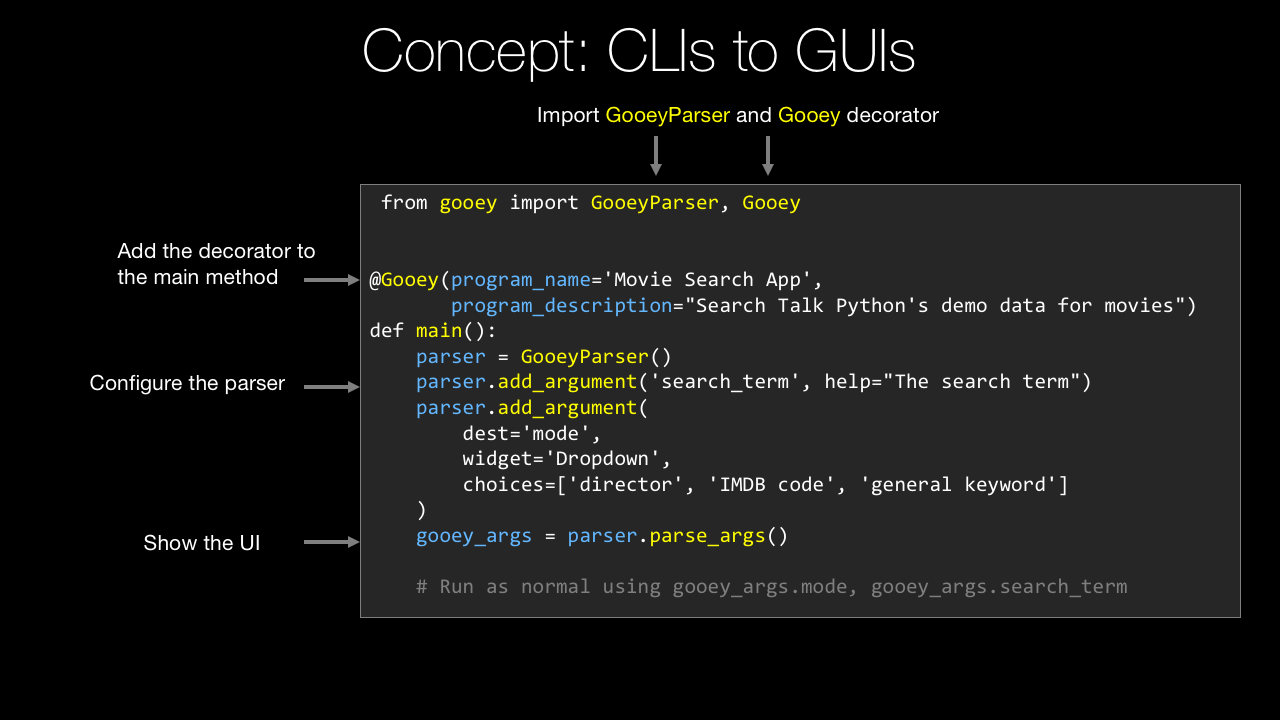

GUIs and Python, they typically don't go together, but in this course, they do.

You'll see in just a few lines of code that we can create a really powerful and cool GUI or desktop application, and this will run on all the platforms, Windows, Linux, and macOS.

And finally, it's fun to consume APIs, but sometimes you want to build them, so we're going to actually take Flask and extend it to create our very own API and put that out on the internet.

This is a ton of stuff right, isn't this exciting?

Well, it's only a small part of what we're going to cover in this course, so I hope you're really excited, Bob, Julian and I definitely are excited to teach it to you, so let's get to it.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:05 |

You've chosen Python for your #100DaysOfCode.

Maybe you're a Python developer who has lots of experience.

You just want to go through this whole challenge, and that's great.

You probably already know the power and popularity of Python.

But if you're just getting into programming, and you're coming here and saying, "Well, let's try Python for this 100 days.

That seems like a great way." I want to tell you, you have chosen wisely.

So check out this graphic.

This comes from one of the best sources on the internet for popularity in adoption of technology, Stack Overflow.

And the data scientists at Stack Overflow did some predictions and said, "Well, how are the various languages doing over time?

Are they becoming more popular, less popular?" Based on their view into the industry.

And they did this up to mid-2017, and then you can see the gray part where they're projecting out.

One of these languages is unlike the others.

It is just going up, and up, and increasingly up.

Your other best bet is JavaScript, which is barely logarithmically going up.

Java looks like it's topping off.

The rest of them are going down.

So if you're going to focus on something, pick one particular language.

Pick the one that's got all the momentum and the popularity behind it, and that's Python.

Now, you might say, "Okay, Michael, this actually is against all these older languages, C#, Java, and so on.

What about the new languages like Go and Rust?

They're probably even more amazing and more powerful, and growing quicker." Well, let's see.

Yeah, they're growing up, they're going upward, not downward, that's really great.

Swift is going up, TypeScript's going up, Go is going up, but they are nowhere near Python in this graph.

I just want to leave you with these two pictures in your mind that Python is really a great place to put your energy and be learning.

My rough rule of thumb here is I would like to bet my career on things that are going up, not down.

So which one of these do you want to pick?

Well, you're in a good place.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:33 |

Let's take just a moment and talk about how you're going to experience this course.

Yes, it is #100DaysOfCode, but it's not 100 different topics.

What we've done is we've broken the course into three day segments.

So day one, two, and three, days four, five, and six, and so on.

So, for example, on day 10, we're going to introduce a new topic, teach you how to work with it, the ideas behind it, do some live code demos, and then after that, you'll get a chance to write just a little bit of code, 'cause you're going to spend a long time actually watching the videos.

These vary, they would be between 15 minutes, maybe to 2025 minutes on average.

There's a few that are really involved that go out longer than that.

But basically, the first day of any three day segment on a single topic is going to be mostly learning about that subject, writing a little code.

The next day is almost entirely writing code.

We'll have a video for you, it may be just two minutes long, and we're also going to have in our GitHub repository instructions with hints and tips, and things for you to do.

So you'll be able to follow along there.

Then the last day is really about finalizing your code, maybe putting the polishing touches on the code that you wrote on day one and day two.

Again, we'll probably have some instructions to guide you, but if you want to deviate, that's fine.

This is your #100DaysOfCode.

We're just here to support you along the way.

So you can think of this course as 33 three day journeys through it.

And each one of those journeys will go through a particular topic: SQLAlchemy, Flask, Collections, whatever.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:46 |

Hi, I'm Bob Belderbos, and I've been programming since ten years.

And for the last six years, I've been using Python, which is now the language of my choice.

I'm very excited to teach you Python in this course.

We're going to cover a lot of angles, so be prepared to learn a lot of Python.

These days I'm a web developer, software engineer at Oracle, and since end of 2016 co-founder of PyBites, together with Julian, where we blog about Python and do code challenges which we lately have transformed in a code challenge platform.

We are super passionate about getting people to code, have a very hands-on approach and really want people to get to the next level of Python.

And that's why we're so passionate about the #100DaysOfCode and this course because we get you to write a lot of Python.

I'm honored to teach you Python and look forward to our journey.

Hi everyone, I'm Julian Sequeira, and welcome to the course.

I've been coding with Python for roughly two years now.

I currently work at AWS, but surprisingly not with Python.

Python is something I've taken up on the side, and something I'm super passionate about and absolutely love doing in my spare time.

I'm co-founder of PyBites, along with Bob.

And everything I do with Python is purely out of love for the programming language.

And I'm totally looking forward to teaching you everything I've learnt over the past couple of years throughout the course.

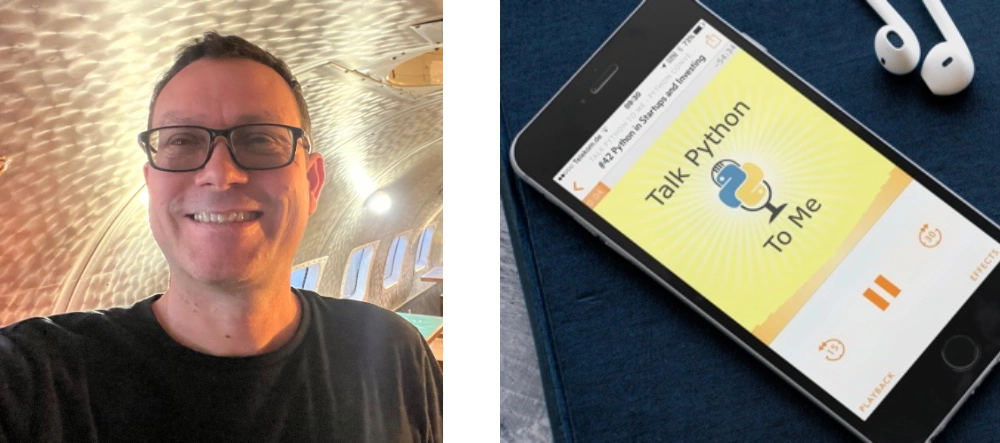

Hey, welcome to our course.

I'm Michael Kennedy, nice to meet you.

A little background on me, I'm primarily a web developer as well as the founder of the Talk Python To Me podcast and Talk Python Training.

I've been a professional developer for 20 years, and I'm really excited to share that experience with you throughout this course.

Welcome to the #100DaysOfCode and Python.

|

|

|

transcript

|

0:39 |

Do you need a little help with the Python language?

Of course, we'll cover much of the little details and definitely the advanced features as we go through this course, but we don't start from the absolute beginning.

What is a variable?

What is a loop?

Instead, we've included a Python language primer.

So when you look at Python, if it's, you know, a little fuzzy, maybe you've done it a long time ago, but you've forgotten.

You haven't done very much of it.

Well, we put something in here to help clear it up.

So anytime you're confused about something in the language, just jump down to the appendix, Python Language Concepts.

Find that thing, watch the one to two-minute video.

Hopefully, that'll clear things right up.

You'll find this at the end of the course.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:09 |

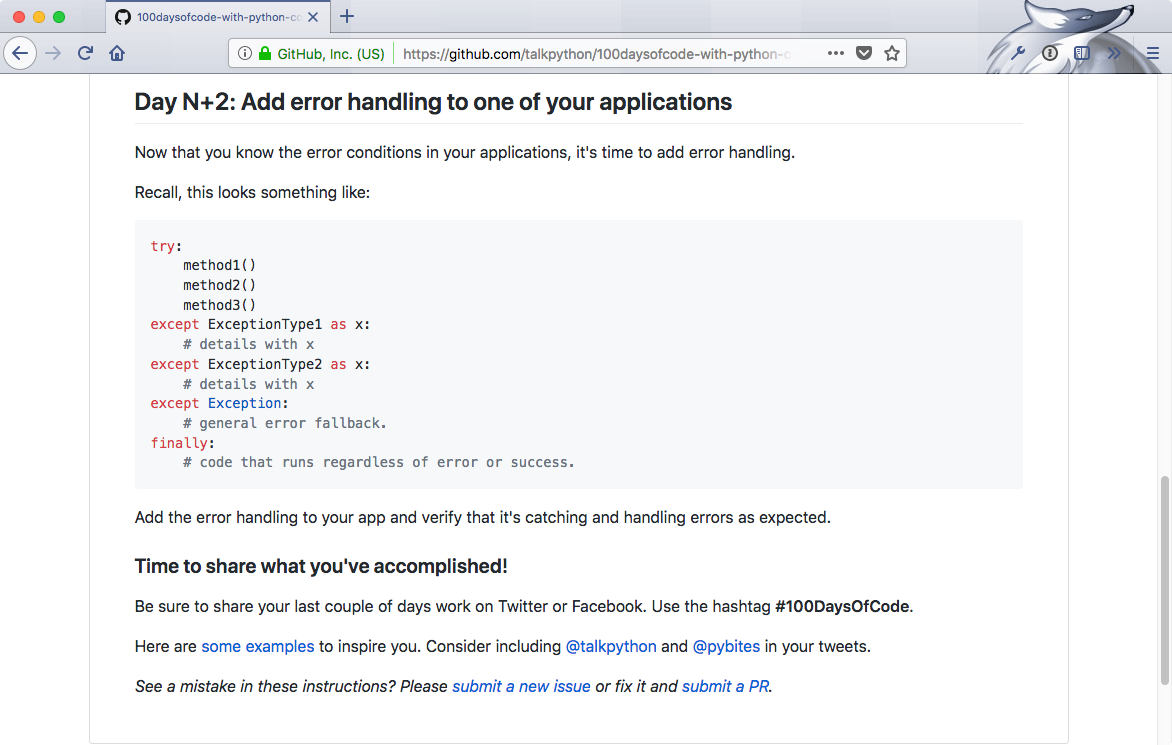

We've made all the code we've written over our 100 days worth of topics available to you in GitHub right here.

gitHub.com/talkPython/100daysofcode-with-Python-course.

You can go over here and check it out.

This is also super important because some of the projects that you work on have either data that you've got to start with, or they've got some instructions and all of that you'll find here.

Let's jump over to GitHub and have a look.

Here we are at the GitHub repository.

You have a little bit of a description here at the beginning.

But the main thing you care about is the days.

You can come in here and see the day one to three.

This is the stuff with JavaScript.

Here's day 13 to 15.

This is our text-based games.

Down over here is a Search API.

Let's just check this one out and see what's in here.

Here's demo that we built, and if you need the code for it you can see actually here's what we've written and so on.

These three pieces work together.

But what's most important is this ReadMe.

It's automatically displayed by GitHub when you come here.

You can see it talks about now that you've seen the videos what do you do?

Here it talks about, okay, so you watch this.

And the first thing on the day 43, that's the first day of these three, this is what we're going to do.

On day two, it talks about working with API.

It shows you how to use it with this thing called Postman.

And then finally, it also shows you how to build your app, and then finally it says, okay, on the last day, we're going to make it even better.

For the very grand finale, we're going to open it in a web browser if somebody picks something inside your application.

You can see that as you go through you want to make sure that you go to each day, look at the instructions.

They're going to be there to help you follow along, both the code demo we wrote as well as the steps and data that we put together for you.

Of course, to download this, you'll want to download it.

I would also say star and fork it if you have a GitHub account.

You could either come here and copy this and Git clone it if you're familiar, or if you don't want to mess with Git you can just download the Zip file and it will be a folder you can unzip somewhere to work with.

But definitely download this.

You're going to want it locally.

You're going to want to save it.

You're going to use it throughout this course.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:42 |

When you dedicate yourself to taking a course, and carefully working the way that the instructor, the author, is working, you are effectively gaining much of the experience that that particular author or developer has gained through their career, through their jobs.

This course is special because it's taught by three people.

That means you get three experiences in one.

And this is super valuable.

Imagine that you have a job at this place.

You get to work with cool VR gear and on hardware and IoT things.

You'll gain one set of experiences.

But if you took a different job, say, you're starting a fashion start-up with your friend, this woman, from college, and you're just working on this coffee shop.

Being scrappy, working, trying to get venture capital and launch your application, you have a totally different experience than this dude in a VR headset.

Or maybe you go the corporate route, work at Microsoft like this guy here.

He's, you know, working on some new programming, language tooling around Python.

These are all super different experiences.

And these experiences are very positive.

They give you a different perspective and more perspectives on programming.

That's awesome.

How's that relevant to this course?

Well, with the three instructors, we each have a slightly different set of tools.

And slightly different way of working.

We're going to show you next, how each of us gets set up.

What you need to follow along with each of us: Julian, Bob, and myself during our particular segments.

You don't have to work like us, but if you want to do exactly what we're doing, we'll show you how we got started.

And we feel this is super valuable for you.

You'll have not just one experience, but three experiences kind of bundled up into one.

And so on the other side of this course, you're going to have a broader perspective.

And that's pretty awesome.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:44 |

'Kay, guys.

This is Julian here, and I just wanted to quickly walk you through my environment for the duration of the course.

There's actually not much to it, and that's because I'm using Windows, and I really wanted to keep it simple.

Okay, I wanted to show that you don't need to use anything crazy.

Not that there's anything wrong with that, but pretty much bare-bones on Windows, you're able to code anything you want and just get into it, okay.

So the first thing you're going to need to do is go and download Python.

And you can do that at Python.org/downloads.

Okay.

And it will detect you're on Windows if you using Windows, and you can download Python 3.6.4, the current latest version, and install it.

It's just an Microsoft installer file.

It will install to a default path.

You don't have to change anything.

Don't worry about it.

Nice and simple.

And once you're done, you can actually just launch IDLE.

Okay, that's I-D-L-E.

Right?

You type that into your Windows search, and that will actually bring it up into the Start menu.

Right?

Once that's up, you'll see something that looks similar to this, the Python shell, which you can just type in Python code.

Okay?

And you can live code just like that.

This is the Python shell.

Now with IDLE, this Integrated Development Environment, okay, that's what IDLE stands for: Integrated Development and Learning Environment.

With that, you can actually create a Python file.

Okay.

This is actually going to be pretty much a plain text file, but when you save it, it will automatically save it as a .py file.

So your Python file.

That's what I like about using IDLE.

I never have to worry about accidentally using the wrong format.

Okay?

And other than that, you've seen some of my videos that I run my scripts through the command prompt.

Okay?

There's my path to my environment, to where I'm storing everything for this course, and I will just run the scripts straight from there using the Python command.

And that is pretty much the bulk of my setup.

You won't see anything else.

You won't see anything different.

That's it, okay?

So standard command prompt on Windows.

I don't even use PowerShell.

I've go the Python shell here, and I just save the files using the new document section of the Python IDLE.

And that's pretty much it.

So, I say keep it simple.

One day I probably will make the move to PyCharm or something, but for now, I'm happy with this.

|

|

|

transcript

|

3:55 |

I'm using Anaconda for this course, a pre-bundled, Python distribution widely used in the Data Science community.

And it comes with a lot of packages already.

You're not required to use this distribution.

You can also pip install my requirements, which we will see in a bit.

You can download the full version here.

We recommend that you use 3.6.

Really no reason to start a new project in Python 2 anymore.

You can also install Miniconda, which is a smaller version, which only includes the base packages.

And, mainly, what you need to know is for almost all the lessons, I will be using Jupyter Notebooks, which is a great way to experiment with Python code and more in the browser.

It's a great tool to both teach and learn Python.

You can try it out if you want to play a little bit at this point by going to try.jupyter.org, but I encourage you to install it to follow along with my lessons.

To install it, again, the recommended way is to use Anaconda, but you can also use pip install jupyter, and that should get it as well.

And let me show you that quickly.

So, first I need to clone the 100 Days of Code repo.

You cd into that.

At this point you really want to make your virtual environment to work on the project's requirement in isolation to not mess up your global space.

And in every lesson, I have a video how to pip install the requirements for that lesson, but I also have 'em all wrapped together in a requirements file.

So, for all the notebooks, you need Jupyter; and ipykernel, which I will explain why in a bit; and then I listed out the requirements for each lesson.

There are various ways to make a virtual environment.

The classic way is to use pyvenv built in module.

You can also use pipenv, the new way, which should be perfectly fine.

And Anaconda comes with Conda, a utility to manage environments as well.

However, I am used to virtualenv, just the classic one.

So, in this course I am making a virtual environment with this alias: virtualenv -p, pointing to the Python binary that comes with my Anaconda installation, and the name of my virtual environment.

So, let's run that now.

And then you have to activate it.

And that's what I'm doing, that a lot I have another alias, ae, and now I'm in my virtual environment, where I don't have anything installed.

At this point, you can just do it video by video, but if you want to have all the packages up-front, you can do pip install -r, requirements/requirements, and that might take a bit because it's not only pulling the dependencies, but some of the dependencies have other dependencies.

With that done, you can launch a Jupyter notebook like this.

And you can go in today's and do any lesson.

For example, Selenium.

And you can open the notebook like this, and you can follow the lesson.

And you see that the notebook discovered my virtual environment.

If that is not the case, you might have to tweak it a little bit, and that's why I pip install ipykernel and Tornado was pulled in as well.

That should have been enough.

If that's not the case, you might have to run iPythonkernel install <username> <projectname> And this will be venv, or the name of the virtual environment.

And then back to the notebook.

You should have the kernel, venv, or whatever you named the virtual environment, here, and you can switch to that, but I already have it here.

So, then your dependency should work.

It's in your virtual environment and you can follow along with the lesson and make any modifications in the code and experiment and that's how you learn.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:46 |

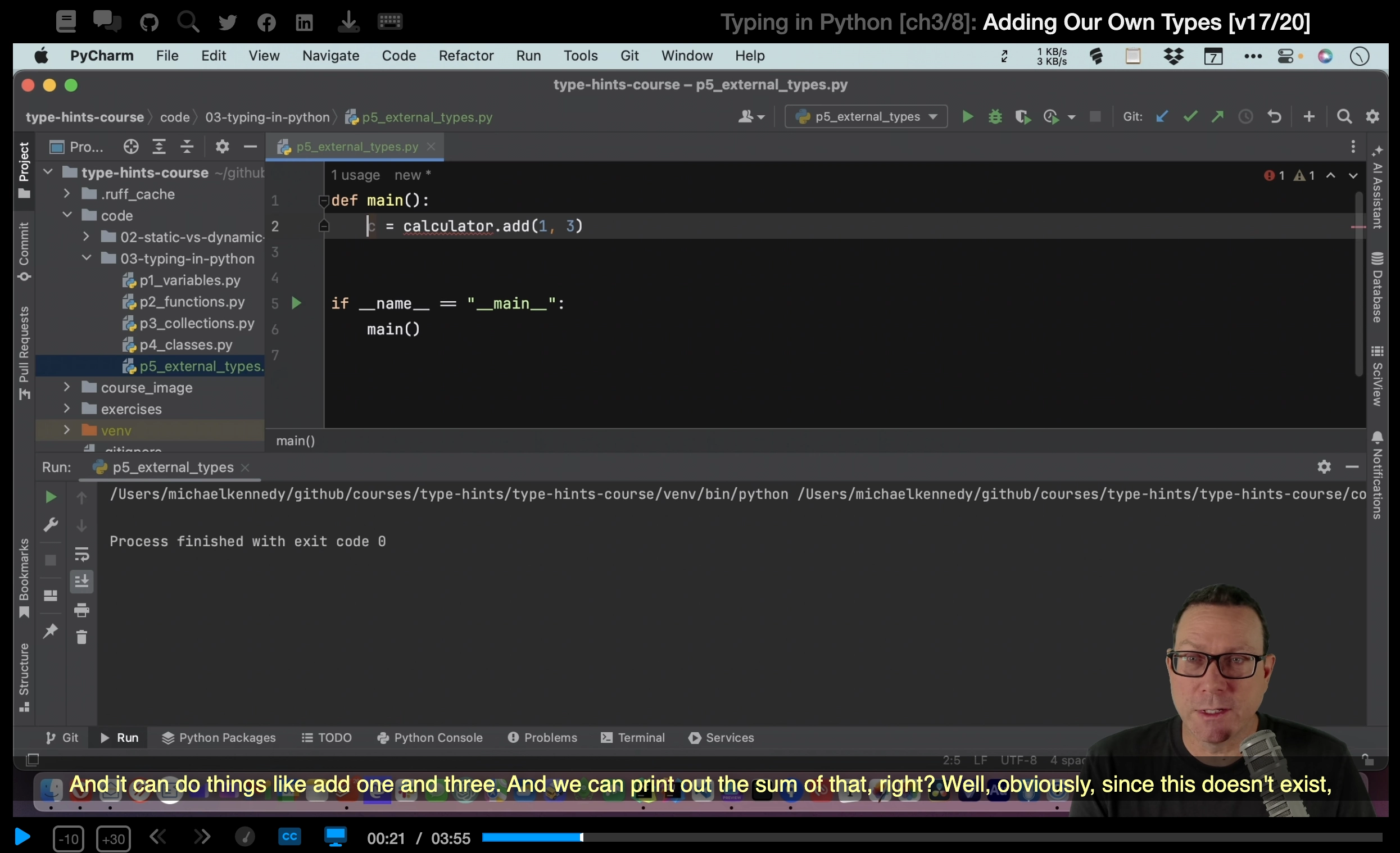

Michael here.

It's time to show you how I set up the tools when I'm writing code.

Now, I'm going to be using a Mac, macOS High Sierra for this course.

That's the latest at the time of the recording.

However, you can use Windows, you can use Linux.

They're all basically the same as far as that goes.

I'm going to be using the editor PyCharm and I'm going to be using Python, the one that I got from Python.org not installed any other way.

So let's see how that goes.

First off, when you're on a Mac if you've taken no actions you don't have Python 3.

You'll know if you open up your terminal.

Come over here and type Python3 -V and you would get the same error something like Python3 not found as if there's a Python4.

Someday, maybe, not right now.

So if you type Python3 -V not lowercase v and you get not found you need to install it.

If you get something like, 3.5 or above, you're fine, you're done with Python.

All you got to do is come over here, go to downloads, download right now the latest is 3.6.4.

So download that, it gives you an installer.

Run the installer; you're good to go.

The other tool that I use a lot is something called PyCharm.

It's an editor for Python.

One of the richest and most powerful editors.

And I really think it's great both for beginners and for professional developers.

And it comes in two versions.

You can see the full fledge Professional or the Community Edition.

So you can download the Professional or the Community Edition.

The Professional one costs money.

You can pay for it monthly or you can buy a license.

Whatever, it's like about eight or nine dollars a month.

You can get the Community Edition.

It's free and open source, okay.

This also comes with a month long free trial so you can try it.

If you care about the features, say which one comes in which, you can compare them down here at the bottom under choose your edition.

So it's up to you which one you get.

So we can come down here and download this and install it.

One thing that's cool that you might consider getting is this Toolbox App.

This one will sort of keep track of updates for you.

It looks like this and it gives you access to all of the tools that JetBrains has.

So if you're going to install more than one, this might be handy but you don't have to get it.

Either way, get either PyCharm Pro or Community Edition or get this JetBrains Toolbox which I have up here.

You can see apparently there's an update for my PyCharm Professional.

If I want a data grip, I can just click that and install it.

Once you have it you can run PyCharm and you'll be able to start creating and editing Python projects.

That's it, I don't really have anything else installed for working with the code.

It's just Python, my OS, and PyCharm and we're good to go.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:22 |

As Michael stated, there are 2 important rules for the 100 Days.

And it is code an hour a day, and track your progress.

Do a daily tweet of what you have accomplished that day.

In order to help you guys do that for this course, we made a feature on our code challenges platform.

So head over to codechalleng.es and sign in with GitHub and go straight to 100DaysOfCode.

So here you see a template where you can start the #100DaysOfCode, but we made it easier and made a direct link to populate the 100 Days for you.

Head over to start talkPython and here you get a grid of 100 Days with exactly the materials of each day.

So for example, Day 1 you start with day times.

Day 1 is a lectures.

Day 2 is the practice, and Day 3 is even more practice.

And you can just click on the Tweet icon and that prepares a tweet for you, so you can just tweet this out or you can modify it as you want.

And then you can start to put things into complete.

So here for example I hit Day 1, done.

And you see that this percent counter then goes up and the items that you've done are under done.

And so, 2.

And here you can document additional learning, so here I learned that time Delta, for example, and here you are at the second lesson.

So this is Day 4 and here you're going to look in the collections module, here.

Watch the videos.

And on 4% and here I did an exercise, and marked complete.

So this is the grid of the whole 100 Days.

All the materials we have prepared for this course, and once you're done, you have a nice love of all the stuff you have coded and accomplished.

For example this is our #100DaysOfCode which I imported from Twitter.

As you see we did a ton of coding and you have it all nicely in one place, and you can refer back to it which we do often.

We go back to our script a lot, pull out stuff we learned, reuse it, and that's why it's nice to have a #100DaysOfCode log.

Apart from that the tweeting is a very easy and we encourage you to do that.

It's also a way to notify us what cool stuff you are building for this course.

Completing the 100 Days is not easy.

It's a lot of work and dedication, but at the end, it's a great accomplishment.

And you will have grown as a developer.

So you should be proud when you see this honor of accomplishment when you hit the hundred percent done.

So we hope this will help you make it easy to keep track of your progress during this course, and if you want to tweet along is stated in one of the rules.

This should make it very easy.

Alright and with that good luck and prepare to learn a lot of of Python.

|

|

|

|

20:34 |

|

|

transcript

|

0:40 |

Good day, this is Julian Sequeira and welcome to the course.

We're going to open things up with playing with datetimes.

Probably not the most interesting thing for most of us and if you're like me, you probably hate it because they can be very finicky.

So, with datetimes I wanted to run us through some of the more basic concepts of it.

Just go with it, there will be more advanced stuff coming up but for now we're going to stick with just the basics to get you through with datetimes specifically around datetimes.date and then datetimes.timedelta.

So, we'll flick through into that, carry on, and let's get started.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:33 |

Right a quick overview of what we're doing for the next couple of days.

For the first day of your datetimes lessons you're going to watch the videos, okay?

A couple of videos for you to watch to do with datetime, date, and timedelta.

Alright after you've done, after you've completed watching the videos go ahead and just play around in the shell.

So do some timestamp calculations as per the content in the videos.

So we won't dwell on that too much.

The second day I want you to head to our challenges, our challenges platform I should say and sign up with your GitHub account.

It's free and then follow this link here and this will unlock this datetimes challenge, okay?

This bite here is going to be based around parsing dates from logs.

Okay so have a play with it, code in the browser and have fun.

That's your day two.

Then day three.

That is all going to be up to you.

Create something for yourself.

I reckon you should give a Pomodoro timer a chance.

Use datetime for it.

I know you can just use a time module for these examples here but the idea is to include some timestamps.

Do some calculations and see what you can wrap around date time okay so the Pomodoro timer is quite simple.

You can do that or you can do a stop watch.

Anything like that.

So if you have any ideas yourself now is your time to test it out on day three.

|

|

|

transcript

|

8:12 |

Given datetime is part of the Python standard lib, we don't actually have to do any setup here.

You'll see in the coming videos that you will have to do setup steps, create virtual environments and whatnot, but given this is datetime, we don't really have to.

And, I think it'd be best for us to just work in the Python shell here.

This is IDLE, the default Python IDE that it ships with.

So, let's have a play with that.

Now, the first thing we're going to do is we're going to import datetime.

But, we're actually going to do from datetime import datetime, okay?

And, this is just going to make it a bit easier for us when we're typing in the rest of our code.

And, just to get yourself prepared, let's just from datetime import date that's for a bit later in this video.

Alright so what is datetime, alright.

For those who are unaccustomed and unaware datetime is just the Python library module that allows you to deal with dates and times.

Pretty self-explanatory, right?

So, if you want to deal with just the dates so, you know, today's date, let's call it the 23rd of February 2018, not very specific.

Or if you want to deal with the time that you've got to think about that from a programming perspective, there is a difference, okay.

So, datetime allows us to deal with the entire time set, the entire timeframe.

You're talking seconds, minutes, hours, days all the way through to years, okay?

We can visualize that with datetime.today().

If we hit enter, there we go, we can see today's date.

The 24th of February 2018 but we also get this timestamp.

It's 10:17pm and these are the extra seconds here.

So seconds, milliseconds and whatnot, okay?

Now I'm going to show you this, what kind of an object is this?

Well let's go, well first actually we have to assign that to something that way so, we'll just go with today.

Here's datetime.today() alright and then we'll type it out, so type today.

So it's a datetime object, okay?

And that's important because you can't mix these objects.

I'll point that out in just a minute.

So with this timestamp, there is more you can do with that.

And I'll show you that in the next video with timedelta.

Alright, but for now just understand that this is what your standard datetime format will look like.

This is the sort of data you're going to get back.

And this is really useful for times when you want to deal with say, subscriptions or anything like that where it has to do with exact timestamps, or logging or anything where you need to know the time that something happened.

Going by the date of say, the 24th of February is not accurate enough, okay, there is 24 hours within that day so, a lot of things could have happened.

Alright, so we'll move on to the date part here.

So we'll just go today date, we'll create that variable.

Here's date.today(), so you can see straightaway we're not using datetime, we're using the date section okay, we're using the date option here.

So date.today() and if we type that out Today date, we can see the different type of object here.

First one was a datetime and now it's a date object, okay?

And we can see what that looks like with today date.

And we have just the date string, okay?

So we don't have the extra time on the end.

And this is, again, very useful.

So you can see the distinction between the two of them.

Alright let's get ourselves a little bit of white space.

Now one really cool thing that I love about date is that we can drill into it a little more, so we can go today.month is 2.

So you can see we can actually tear it apart a bit.

So today.day is 24 and then today.year, and we get 2018.

So now you can sort of visualize how date can help you in your projects, right, if you're not already using it.

It's actually really cool.

So one really, really cool thing that has come in handy over time, is the fact that you can do a bit of math with your dates, alright.

So we'll go, let's just go something easy.

So Christmas, what's the date for Christmas?

It's the, we'll go year first, so 2018.

It's the month next, so 12.

And then it's the day, so 25th, alright.

Now one thing, if you had a look, this is ...

us specifying a date, this is us assigning a date to a variable.

So now the Christmas variable is always going to have this date assigned to it.

You can see that there, okay.

Now, this is really cool, so We can actually go Christmas, cause we know that's the end of this year, minus, today date.

Kay, and that's 304 days, it automatically called on timedelta, so that's giving away something for the next video but, carry on, 304 days.

Alright, and we can see that visualized a different way.

We can, and this is again giving more away we can go Christmas minus today in days, so .days.

304 days, alright and this is really cool for something such as this, I'm just going to copy and paste here rather than type it all out for you, alright.

So if Christmas is not today date well what can we do?

We can print a certain message.

Again, you can see this is useful for certain other projects so print, sorry there are still this many days (christmas minus today).days, until Christmas.

Okay, and then else ...

We'll copy and paste this as well.

We're going to print some sort of message, alright.

"Yay, it's Christmas." So, by hitting enter, sorry there are still 304 the same value here, until Christmas.

I've obviously left out the word 'days' so that's my mistake, but sorry there are still 304 days until Christmas.

If I happen to wait another, you know, ha ha ha ha that many days, 304 days we would then get this message here.

So this is date and this is datetime.

Very, very tedious at times, I want to say but so useful, so this is a great place to start manipulating your code, manipulate your dates and have some fun with it.

And in the next video we're going to look at datetime.

|

|

|

transcript

|

6:07 |

Okay, just like the previous day, we're going to look at something but we're going to use the Python shell for this one.

And specifically today we're looking at timedelta.

So what is timedelta?

Well, timedelta is pretty much a gap in time measured out.

So, for example, if you want to calculate something such as how many hours from now until a certain point in time, you can use timedelta for that to specify what it's going to be.

A real world example.

How many hours until I go to bed?

Well, let's say it's going to be four hours.

So my timedelta, you can specify for this calculation, is four hours.

And four hours from now could be two in the morning, okay?

So it's different...

That's how you calculate things like that, you use timedelta.

All right, so how do we do that?

Well, we go from datetime import datetime just like usual, from datetime import timedelta.

All right, so let's represent our timedelta as a variable t timedelta and let's work on days and hours.

So let's say we have four days and 10 hours until my next day off work, it's pretty depressing.

And how do we deal with this?

How do we work with this?

Well, let's first of all confirm we have a timedelta object there, excellent.

And what next?

What can we do with this?

Well, we can go how many days in there.

So t.days.

That gives us four days, okay?

One important thing to note here, watch this next one.

T.seconds.

36,000.

So 36,000 seconds is not four days 10 hours.

36,000 seconds is just the 10 hours.

And why is that?

Well, this timedelta is just like...

Imagine the stopwatch on your watch, it's only able to go up to a certain amount of time, right?

Maybe 23 hours and 59 minutes.

So with timedelta, the seconds, it's only able to go up to a maximum of one day, okay?

So we have four full days here, so it's not going to show us the seconds in four full days.

It's only going to show us the seconds in the hours.

So you have to take that into account and your calculation.

Okay?

We could calculate the hours but not like this.

Okay?

It doesn't allow us to do this because it has seconds, it's not going to bother with hours, all right?

So in order to get around this, well, you have to do a bit of maths, unfortunately for people like me.

So t.seconds divided by 60 and divided by 60 again.

Well, because we have 60 seconds in a minute and then 60 minutes in an hour.

And that gives us that 10 hours.

Alternatively, you could write that as t.seconds / 3,600.

Same thing, okay?

That's a really important gotcha because it definitely got me.

back at the start.

So here is an example of a sort of scenario you could use it in, but just keep in mind, timedelta is that gap, it's that sort of way of representing the time between two points in time, okay?

All right, so we have an ETA.

Well, let's just say it's the ETA until I wake up.

So hours equals six.

We're not even going to talk days here, okay?

We can go today.

We'll give ourselves a datetime today, variable, okay?

We're not dealing with just date, we're dealing with day time because we want the time, we want the minutes, the seconds, the hours, right?

So there we go, we've got two variables, ETA and today.

All right?

So today, let's just show you what that is.

It's currently 10:39 p.m., okay?

Let's get rid of that.

All right.

We can go what is ETA?

Is our timedelta, all right?

Now, what next?

We want to add these two together, okay?

So we can go today + ETA, this is the beauty, the absolute beauty of timedelta, we can just add it straight to a datetime object which is so cool and so handy and it makes it so easy.

So today plus ETA.

And look at that time.

It actually changed the date to the 25th because we'd cross over midnight and it says six hours from now is 4:39 a.m., okay?

And this is really, really cool because you don't have to worry about any conversions, you don't have to change anything.

It's so easy.

And even better than that, we can format it, so today + ETA as a string.

Look at that, it's glorious.

We have an actual nicely formatted date string and time stamp.

How awesome is that?

And that's timedelta, that's really the bread and butter of timedelta.

You're dealing with just setting yourself a static time, a static amount of time and then you can add it, subtract it, do whatever you want with it.

And this is really useful in a lot of programs, so keep this one in your belt

|

|

|

transcript

|

4:02 |

Okay, and that was the basic overview of datetimes.

How cool was that?

Not too bad, not too hard.

Nice way to start your #100DaysOfCode on Python, right?

Alright, so let's do a quick recap of what we covered.

There wasn't a lot so this will be pretty quick.

So we began by importing datetime and date.

And we then started to look at the differences between datetime and date.

So a datetime object, well when we ran datetime.today(), it included the date and the time, so we had a timestamp in that object.

Whereas when we ran that with just date, we only get the actual date, the calendar date.

So we the 19th of February 2018, alright.

And we found that you can't actually easily combine the two, do maths between the two.

Okay, not without a lot of conversion.

First we gave ourselves a Christmas variable, and we gave it its' actual date, which is something you can do with date.

You can assign an actual date to an object.

Once we did that, we were then actually able to calculate the amount of days between Christmas and the current date.

So that was just a bit of a little scenario for you to use datetime and date.

Okay, next we played with timedelta.

Now we began by importing timedelta and then we gave ourselves a timedelta object.

So we set the timedelta length as 4 days and 10 hours.

Then we discussed the fact that you can view your timedelta in those days and you can view it in seconds, but you can't view it in hours, okay.

And that's because it only works in days and seconds.

And the seconds only go up to a max of the 24 hours of a day.

They expect you to do the calculations yourself.

And that's what we see here.

t.seconds / 60 / 60, and then we get our ten hours, okay, matches up there.

As a little scenario to try, we wanted to look at the ETA.

We wanted to add the estimated time of arrival onto the current time.

So the current time plus six is that there, that's the object there.

That's the response there I should say, the calculation.

And we were able to add and subtract timedelta from datetimes which is really, really cool and makes it really easy.

And using string on that, converting it to a string, we got a really nicely formatted timestamp here.

Very useful for log files right.

Alright, your turn.

This is where it gets a lot of fun.

What I'd like you to do for day three is come up with something cool for you to make with datetime or timedelta.

Think about perhaps making it a stopwatch, maybe a timer application.

I actually think a really fun one to make would be a Pomodoro timer.

So if you're not familiar with Pomodoro, just go and google it.

But that would be a really cool way of setting specific timestamps that a user could choose using datetime and what have you.

So that would be really, really fun.

Now I know what you're thinking, datetime is a really deep and in-depth topic, but unfortunately we just don't have the time to run it in this course.

So I hope you really enjoyed it.

Move onto the next video, we are keeping it nice and simple for the first day.

Expect things to take it up a notch going forward.

So enjoy, get cracking, don't waste any time.

|

|

|

|

17:10 |

|

|

transcript

|

0:40 |

Welcome back to the 100 days of Python.

In the coming three days I will guide you through the collections module, a very convenient module to work with more advanced data structures.

First we look at namedtuples and how they can make your code more readable and elegant.

Next we look at defaultdict, which is convenient to build up a nested data structure.

Third, counter, saves a lot of code to find the most common thing in a collection, and lastly, deque, which can tremendously improve your performance based on the operations you want to do on your sequence, and for the second and third day I got a movie dataset where you can put the collections module into practice.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:05 |

Get Pythonic with a collections module.

We are all familiar with dict, list, set, and tuple.

The collections module adds a few other specialized ones that are very useful.

Let's import the modules we're going to use.

A namedtuple is a convenient way to define a class without methods.

We all familiar with a normal tuple, which you can define with parenthesss, and one or more elements.

The thing with the classic tuple, though, is that the order is not really meaningful, so if you print the user name and the user role, user index zero is a user index one, and you already notice that the indexing is not really saying that much.

Is there a more readable way to define these kinds of tuples?

And yes, you can use a namedtuple, so let's define one.

User equals namedtuple, and you give it a name, and the fields or arguments it takes, so name and role.

And let's create a user, with user and I give it a name Bob and role equals coder.

The nice thing, then, is that you can access the entries like this, instead of indexing with zero, one, etc.

So this is much more meaningful And to see that in a print statement.

So, use namedtuples.

It's very easy to set up, and it definitely makes your code more readable.

|

|

|

transcript

|

3:01 |

A second data type I want to show you, today about, is defaultdict.

And it's very useful when you're building up a nested data structure and you have to account for keys not being there.

Now first of all, what's the problem with keys?

Let's define a very simple dictionary, just one user and role, and let's do a lookup by key.

So...

Bob is there.

Julien is...

Oops, not there and that gives you a key error.

There's a way around it by using users get.

Oop, get Bob..

and users get...

Julien...

which returns none.

But how do you deal with that when you're building up a collection?

Now let's get some data.

I'm going to define a list of tuples.

A challenge is done.

And it has...

tuples of name, and a number of the challenge that has been completed.

Let me type that out.

So the goal is to convert this into a dictionary.

Let me show you what happens if I use a normal dictionary.

For name challenge in...

challenges done.

Challenges dictionary...

name append...

challenge.

Oops, it says Mike is not in the dictionary.

In the first round, he is indeed not in the dictionary.

So here is where is you really want to use a defaultdict.

So to define one, challenges...

Equals defaultdict, and you need to define what type the values hold.

So in this case, the key is the user and the value is a list of challenge numbers.

So I put list here and the rest is kind of the same.

For name challenge in challenges done.

Challenges...

Name...

append...

challenge.

I'm almost sure this works.

So, yes, we have a defaultdict which holds lists and here you see keys are Bob, Julien, and Mike and values are list of challenge ids.

So you see here, we work around the key error.

The defaultdict has the mechanisms to use a factory to initialize the data type that the values need to hold and yes, it's safer, it's cleaner, and for this type of task, I highly recommend that you use this data type.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:21 |

Let's move on with Counter.

Let's say we have a text which is split into words, and we want to count the most common words.

Before I knew about collections, I would write something like this.

There you go.

I had to loop over words, keep a dictionary, see if the key was in the dictionary, if not, initialize to zero.

If it's in there do plus one.

Then I had to loop over the items over the key value pairs, sort them and use lambda to sort by value.

In reversed order and take a slice to get it to five.

Now compare that with using Counter, and its most common method.

It's like magic, right?

One line of code, you pass the words list into the Counter, and you call most common and you give the number of top words you want to see and compare that with all the work I had to do here and how easy it gets by using the collections, Counter.

|

|

|

transcript

|

3:27 |

Next up are deques.

deques are stacks and queues.

They're useful if you want to insert and append on both sides of the sequence.

In this section, I will compare them to lists.

I mean, lists are your best friends.

You will use them everywhere.

They're easy to use and for 80% of your use cases, or maybe 90%, they're just adequate.

But lists come with a downside which if you have to move items around, they get less performant.

And in this exercise, I will create a list and a deque of ten million ints and a function to do random inserts and deletes and then we're going to use timeit, to see how they perform.

So let's create the two sequences.

First I want a list.

I can just use the range.

Let me the get the zeros right.

One, two, three, one, two three.

That's ten million.

And let's make a deque.

You create that big deque.

Range, one, two, three, one, two three.

Next, we create an insert and delete function that takes a sequence...

and we do, for...

Underscore...

In braces..

Index equals random...

Choice.

And a random choice takes a sequence and just randomly chooses one item.

I store that into index and I remove it.

So that index is like a random location in the sequence.

I'm going to remove the item that's at that index.

And I'm going to do an insert of index at index and I'm just going to insert the same value of index, doesn't really matter.

I'm going to use timeit to time this function for both the list and the deque.

Here we have the timeit module.

And we're going to call it with insert and delete on the list, and the list we defined here above.

You can see this took a little bit.

And now let's do the same for the deque which we defined here.

And although it seems to take a little bit as well.

Here we're talking about milliseconds and here we're talking about microseconds.

Here it also run like 10,000 loops.

This one was slower so it reduced to one loop.

So deque performs at a fraction of the list and that's because inserting and removing at both sides of the sequence are more efficient in a deque than a list.

A list has to move all the items around and that's expensive.

I encourage you to look at the docs because there are a few other data types that are interesting and you can read about ChainMap, for example.

An OrderedDict is another good data type to know about.

Although I think in Python 3.6, dicts are becoming ordered by default.

That concludes day one.

|

|

|

transcript

|

0:54 |

So a quick overview of we've learned so far, namedtuples, an elegant and readable way to create tuples, and instead of user index zero, and index one, you can say user.name and user.role.

A defaultdict is great way to buildup a nested data structure, you don't get key errors, because the internals make sure that the value gets initialized before appending to it.

Counter, don't reinvent the wheel, so here at the top you see all the code I needed to get the top five words in a string, and below we did the same, but only with one line of code, very powerful.

A deque, so lists are your best friend, but if you have to insert at them at the start, for example, they get very slow.

So deques are great if you need to insert and remove at both ends of the sequence.

And now it's your turn.

|

|

|

transcript

|

4:39 |

Welcome back to the 100 days of Python and the second day of the collections module.

Today, we're going to get practical with a code challenge.

That will be highest rated movie directors.

We will load in a data set and convert it into a default dictionary of directors as keys and movie namedtuples as values.

If you want to try it yourself on scratch, I encourage you to pause the video now and read through this link and try to code it up yourself.

What I will do in the rest of this video, is to guide you how to get the data loaded into the directors variable.

So parse the CSV, convert it into defaultdict, and also will have a Counter example, how to get the directors with the most amount of movies.

So if you need some guidance, keep watching but maybe you want to try it yourself first.

Welcome back.

I hope you had fun doing the other exercise.

In the next session, I will show you how to load in the data and parse it into a defaultdict.

So we're going to load this data in and the goal is to make a defaultdict where the keys are the directors and the values are a list of movies and every movie will be stored in a namedtuple.

So let's define the namedtuple first.

We've defined a namedtuple called movie with title, year, and score.

Those are the only fields I'm interested in for now.

We need to parse the CSV and load the data into defaultdict.

I'm not going to touch too much upon the CSV part because there's a whole lesson dedicated to that.

I will write out the function and come back and comment it line by line.

And let's see if that works.

And let's get the movies of Christopher Nolan, one of my favorite directors.

Wow.

Look at that.

I can look up a director and I get a list of movies and each movie is a name tuple with title, year, and score.

Okay, let's go back to the code I've just written.

We make a function and receives data which by default is movies CSV which we retrieved here.

I initialize a defaultdict of lists called directors.

I open the data with a with statement.

Then I use the CSV dict reader to parse every line into an OrderedDict.

Every line, I extract the director name, movie title, title year, and IMDB score and store them in variables.

The year, I convert to int.

The score, I convert to float.

With data analysis, there's always bad data and this is no exception.

A value error got raised for some rows.

So when that happens, I just ignore the row.

I'm not interested in incomplete data.

I initialize the movie namedtuple and give it movie, year, and score.

That namedtuple gets appended to the director in a directors named list.

So here you see the defaultdict in action.

I don't have to initialize an empty list for every director up front.

defaultdict handles that all behind the scene.

And then I return the directors defaultdict.

Then I call the function and store the results in the directors variable and then I can look up directors.

So there's a lot of stuff you can do with this data.

Let's do one more exercise.

I'm going to use Counter to find the directors that have most movies in this dataset.

So I use a counter and I'm going to loop over...

the directors...

we stored before.

I can loop over dictionary with items which gives me the value pairs.

Then I'm going to store the director...

in the counter object.

I'm going to sum up the length of the movies.

You can do this by hand, but the nice thing of having a counter object that now I can do counter...

Most common.

Five.

And there you go.

Spielberg, Woody Allen, this is pretty plausible.

So here you got some more practice using the collections data types.

|

|

|

transcript

|

1:03 |

Welcome back to the 100 days of Python, and the third day of the collections module.

Now it's time to get some more practice yourself, so I encourage you to try to use the new collection's data types in your scripts.

We did the #100DaysOfCode ourselves and we made a module index script which lists all the modules we used and the days we used them, so you can go to our log and look up those days and look at the scripts that used the collections in one way or the other.

This was the script to identify if a tip was already submitted to pytip, and here we use the name namedtuple.

And this was the script I was just showed you about the module indexer, and here we used defaultdict and Counter.

So you can look at more examples for where we used those data types, but maybe you can refer to some of your code to start using collections more.

And don't forget to mention 100 days of Python when you tweet out your progress.

That's a great way to keep on track.

Good luck, enjoy, and remember, keep calm and code in Python.

|

|

|

|

24:41 |

|

|

transcript

|

0:25 |

Good day everyone.

This is Julian Sequeira and welcome to Python Data Structures.

So this series of lessons in going to walk you through the basics of lists, tuples, and dictionaries.

So hopefully stuff you've seen before, but this should be a good refresher.

There'll be a couple of videos to watch, but then there'll be some exercises as well.

So, nothing left to say.

Let's get cracking.

|

|

|

transcript

|

2:47 |

Here is your three-day breakdown for this lesson.

It's actually pretty simple.

There's not much to it because we are dealing with data structures.

Super important though, so very important that you get this down.

For the first day, we're just going to watch the videos.

Okay, there's not too much involved with this.

Just watch the videos that we have on lists, tuples, dictionaries, and then just have a play in the Python shell.

There's really not much to do.

So digest the content in the videos and then hang around for day two.

Now the second day, it gets a bit more interesting.

What I'd like you to do is follow this link here, this bites of Py code challenges promotion link.

This will give you free access to this specific bite.

This is a little challenge for you.

We just open it in a new tab.

Okay, I will log in with GitHub.

So you have to have your GitHub account ready.

And there you go.

So I'm already a premium member obviously, but this will unlock this bite for you to work on if you are not already a premium member.

This here is regarding dictionaries.

So have a good play with this.

Enjoy the challenge.

Work on it in the command line within your browser and do that for day two.

Back for day three, this gets a little more tricky.

What I'd like you to do is a bit different as well.

I'd like you to go into this data.py file which is here in the repo.

And I'd like you to just have a quick look at the dictionary and the lists that are in there.

It is pretty much a list of just the United States states and the acronym used for them.

So what you can do then is complete each one of these little tasks, okay.

It will involve you actioning or working against the list in the dictionary, pulling out data and just playing around with them.

So you'll need to pull them into some, whatever script, import them to whatever script you'll be running this from.

And just remember that dictionaries are unsorted so that should make this a little more tricky.

Alright, so that's your day three.

Just playing around with that data.py file.

Obviously if you want to play around with it in any other way, go ahead, feel free.

But this is just a couple of quick, these are just a couple of quick tasks for you to do that should give you around 15 or 20 minutes worth of practice which is what we're aiming for.

So enjoy, these are your three days and let's get on with the video.

|

|

|

transcript

|

7:35 |

Lists are actually pretty simple.

They're probably one of the things you're going to deal with the most in your Python journey and the easiest way to demonstrate it is to just create one right here of numbers.

So let's create a stereotypical list, all right.

We do that by using the square brackets and we're going to create five entries in that list.

So this list contains five items.

Okay.

Now, because we're dealing with numbers specifically, we don't have to put the quotes around it, okay.

If we were dealing with strings that's what we do, but we're dealing with just numbers so let's just leave it plain like that.

So that's our numlist.

We'll just call it back so you can see what it looks like.

There you go.

So it's now a list of five numbers, okay.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

One of the cool things you can do with a list is you can actually reverse it.

Okay.

So, now need to write some nifty code that will go through, parse it, and put all the values in back to front.

We can just do numlist.reverse() Call numlist back and there you go, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Now we can do that again.

Okay, and we're back to one, two, three, four, five.

Now, if we actually go back, one thing we can do, is we can actually sort the list.

So numlist.sort(), okay.

And there you go 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 again.

And this is very handy because you can actually sort with letters as well.

Now let's say we want to actually print out all of the values inside num list.

How do we do that?

We can use a four loop, okay?

So we can go four num in numlist, print(str(num)).

So we hit enter and there are our five numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 So it's pretty powerful.

There's with just this basic ideology you can get a lot of stuff done in Python code.

Now one of the other ways you can actually create a list is to call the list function against a certain string.

Let's say we have a string called - we have a variable called mystring.

And we assign it to string Julian.

Okay, so mystring is Julian.

Well how do we convert that into a list?

We simply call list against it.

So list(mystring) is Julian.

And there you go, you see my name has just been chopped up so that each letter, or each character I should say, is now a string value inside this list.

Right.

So, what can we do?

We can assign that so l = list(mystring).

So we're assigning this here to the variable l, alright.

And we'll just call that back.

And it's Julian.

Now what are some interesting things we can do with this?

Well, there's actually quite a lot.

We can actually reference the values by their position, by their index, inside that list.

So we can go l[0] is J.

We can go l[4] is A.

You can see we got J there, we got A there.

Very handy.

What else can we do?

Well there are a few other functions we can call here.

We can go pop, and what pop will do it's actually going to return the last letter from this list.

So, the letter N is going to be returned.

But at the same time, it's going to be removed from the list.

So my name is now Julia.

Right.

We can then insert it back in.

And we use insert for that.

Now when we insert, we actually, if you look at this tool tip here that's cheating, you can see we have to specify an index and then the object.

So what position are we inserting the letter N into this list?

Well, we're going to insert it into position 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 5 is going to be on the end, so position five.

And what are we inserting?

We're inserting the letter N.

All right, it's an actual string.

Now when we call the list, there we go, it's rebuilt with the letter N.

Another interesting this we can do is we can actually replace any of these with any other letter.

So we can go l[0], which we know will actually return J, but we can replace J.

So L[0] is going to be B.

So, l is now Bulian.

Okay?

Ya, a little play on words.

Let's go with that.

Now if we wanted to get rid of the B, we could actually delete it or we could pop it.

The difference is, as I've said before, pop will return the letter in that position, where as now with the delete option it will actually delete it.

You won't even know what you're deleting.

It doesn't return anything, it just deletes.

So if we want to delete that zero we just have to type del(l[0] and there's the B gone.

All right?

Next we can do l.insert().

We'll choose index position zero.

And this time we'll put an M in.

l is now Mulian, okay.

And now, even better, with pop, let's say we do want to return something, we can go l.pop(), but now we can actually specify a position, an index.

So we can go l.pop(0), we get the M returned, and the M has also been removed from position 0 in the list.

So those are some cool little nifty tricks you can keep up your sleeve, add them to your book, because when it comes to lists, you'll end up dealing with them quite a lot.

So knowing how to pop and how to delete and insert and append, which is another one I'll show you quickly.

l.append(), let's add S.

We can append, append will always add right at the end into the last position.

So definitely keep all of these handy.

You'll be using them quite a lot.

|

|

|

transcript

|

3:07 |

If you're learning Python you're going to come across two words that may or may not make sense to you, and they are mutability, and immutability.

Okay, type them out on screen, mutability, immutability.

And what do they mean?

Well, mutability means it's something that can be changed, it's an object that can be changed.

You saw in the previous video that we were manipulating the mystring variable, and we were dropping j, we were dropping n, we were doing all sorts of things to that list.

Now, immutable lists, okay, let's just go with that for one second, are lists that cannot be edited, so if you tried to edit it, if you tried to pop out that j, or pop out that n, you'd actually get an error, and they're not actually called lists, they're called tuples, okay, you've probably heard that terminology by now, but we're just covering it again, and I'll just quickly demonstrate the difference between the two.

So we're going to say l, again, for list, is a list of mystring, so we can see mystring is my name, okay, and t for tuple is a tuple of mystring.

So let's just show what the two of them look like.

And the big difference here is you've got the square bracket versus the rounded bracket, and that's the telltale sign that you're dealing with a tuple, okay?

Now watch what happens when we try to edit the two, okay, we can go, l, let's actually overwrite, just like we did in the last video, so, l[0], we're going to assign the word, or the letter, T, so my name is now Tulean, no that wasn't a name I was called in school, so don't laugh, and now if we try and do that to the tuple, we can go t[0], is, let's just go with the B from the other video, and we get this error.

Tuple object does not support item assignment, and that's because the tuple is immutable, we cannot edit it.

We can still talk to it, imagine a hard drive or something, or your SD card in your camera is read-only, that's pretty much what a tuple is, so we can go t zero, we can return that, you know, we can read it, we can talk to it, we can iterate over it we can go, four letter in t, print letter.

And there we go, we can still iterate over it, just like we do with the list, the difference is, we can't edit it, and that is what a tuple is, and that's a demonstration of immutability.

|

|

|

transcript

|

7:21 |

Alright.

Next up we're going to talk about dictionaries, or dicts for short, let's keep saying dictionaries, just to be safe.

And they're made up of pretty much two different things.

The easiest way to demonstrate it is to just create one in its simplest form.

So we'll create a dictionary called pybites, and let's just add a few things to it.

The first thing we need to add is a key, and the second thing we need to add is a value.

Alright.

Looking at it here, there's a separator here, your colon.

And that separates your key, the key comes first, from your value on the end.

Alright, and this here is technically a dictionary.

It may only have one item in it, but it's a dictionary all the same.

Let's make it a little more interesting.

When you're adding a second item into your dictionary, you separate it with a comma.

Alright, so we've got Julian, now let's add Bob, and let's just say he's 33, then we have Mike, let's say he's also 33.

Let's just say I'm being super generous with those ages guys, anyway, there's our dictionary.

So to view what it looks like, we just type in, pybites.

And there it is there, the three different items.

And these link to each other.

So the key is Mike, the value is 33.

The key is Bob, the value is also 33.

Now notice when we printed it out, it printed out in this order.

Well this order is not explicit.

With a dictionary, when you're passing it, when you're listing it out, when you're displaying it, there's no guarantee that the data is going to remain in the order, okay?

That's very important to remember with dictionaries, they are unordered, okay?

Now let's say we wanted to create a dictionary but we didn't know what values we were going to put into it from the start.

We'll just do a quick little side track demonstration here.

You would start off just as you would do with a list that's empty, except you're using two curly brackets instead of the square ones.

So people is now an empty dictionary.

There's absolutely nothing in it.

To add someone to it, this is the tricky part, this is where it gets a bit different.

What you need to do, you need to actually pretty much in square brackets, you need to choose the key, alright?

In this instance the key for a list of people is going to be Julian, and we're going to assign that key a value of 30.

So the dictionary people, we're creating an entry, a key, of Julian, and we're assigning it the value of 30.

We list out people, there we go, we see that exact same formatted dictionary as we did when we explicitly defined it up here, okay?

We can add to it again.

We can go, people, Bob, and we can assign Bob the age this time of 103.

And there we go.

So same thing, right?

This time we just populated an empty dictionary.

But either way it all comes out the same.

Now the way you interact with the dictionaries is a bit different to lists.

The way we view just the keys, just these keys here, forget the values for a minute, is we use keys.

So we can go pybites.keys, and there are our dictionary keys.

Julian, Bob, Mike.

The same things for the values.

pybites.values, and there we go, the three values.

30, 33, and 33.

Now what if we wanted to see all of this?

Now this is all well and good because we're in the shell.

But if this was an actual application you can't just type in the name of your dictionary and expect it to print out, right?

This is just all standard out through the shell.

So the way we would actually print out, first of all, the way we actually see each pair of dictionary items is to use items().

We can see Julian 30, Bob 33, Mike 33.

These are our three different dictionary key value combinations or items.

Now how do we pass over all of that?

Well we do it just how we would with a normal list.

We can go for keys in pybites.keys, print keys.

There we go.

We can do for values in PieBites.values, print values.

Okay?

This is all very similar, you can see the similarities between dictionaries and lists.

But last but not least, what if we want to print out all of this information, not just keys, not just values, without having to run two separate for loops, which would be quite un-Pythonic right?

Well, God love Python, we can go for keys values in pybites.items(), so for keys and values in PieBites.items Print keys, and remember we have to do the string thing here, values, and there we go.

Julian 30, Bob 33, Mike 33.

Now obviously that is not very pleasant on the eye, so we can do our standard string formatting.

So we can go, for keys, values in pybites.items(), print, string is digit years of age, keys, values, okay?

And there we go.

We can see Julian is 30 years of age, Bob is 33 years of age, Mike is 33 years of age.

And that's dictionaries.

It's actually that simple to iterate over dictionary, and that's pretty much it.

You've got your key, and your value.

And you just do it over and over again, just like a list.